The Male Ward 7 of Callan Park Mental Hospital was known as “notorious”. Searching for why, I found out next to nothing. At least, not until I started digging into the patient notes of those who’d been inmates there.

Note: the language used in this story is intended to depict the views and language of the past. I do not condone the outdated terms used. This story is also very much based on a real place.

Warning: this story contains raw depictions of mental and physical health concerns.

Spoilers Ahead!

Author’s Note:

This story, while the main thread is fictional, is based on real places. Peat Island held many children abandoned by their families as a result of disability or illness.

The conditions patients lived in depicted in this story are pretty accurate to the conditions in Callan Park described by journalist Victor Douglas Valentine, who posed as a nursing attendant at the hospital between June 22nd and June 29th in 1948. Valentine was put on a working man’s ward, and as he describes stone rooms I doubt he was assigned to Ward 7, a timber structure.

For Mr Valentine’s original reporting on Callan Park, you can find it archived from The Sun newspaper here:

Part 1: Tuesday, 29th June, 1948

Part 2: Wednesday, 30th June, 1948

Part 3: Thursday, 1st July, 1948

And for more of The Sun’s reporting on the conditions at Callan Park, as well as an aerial photograph map of the main Kirkbride Complex, you can find that here.

As for the Male Ward 7… In 1961, then Minister for Health, Mr. Sheahan, visited Callan Park Mental Hospital. What he had to say about Male Ward 7 described it as an abomination. The whole asylum had a terrible reputation by this point, but Male Ward 7 stood out as so bad, Mr Sheahan ordered it immediately decommissioned.

For why it was so Notorious, this article is the best, and really only, description of it I’ve been able to find on the internet.

But where I’d like to return to, now, is the beginning of Callan Park, as the way it was begun is a poignant and terrible contrast to what it readily became, and the conditions depicted in my story were very far from what the founders intended.

The Callan Park Hospital for the Insane, as it was originally named, opened in 1876, as an annex of Gladesville Mental Asylum (located up the river from Callan Park), and closed, then called Rozelle Hospital, in 2007.

Oddly enough, it’s not the first time I’ve found myself surprised by a defunct asylum. Years ago, living in New Westminster, of the Vancouver area in Canada, I used to jog around an area of new build apartments I learned later were built on the Woodlands site, another former (and horrendous) asylum.

Old asylums are universally notorious today. As I’ve learned, at the time Callan Park was commissioned, they were already notorious. Parramatta Lunatic Asylum and Gladesville Asylum had both preceded Callan Park, and they had shocking reputations. James Barnet, who became Callan Park’s architect, recalled of visiting Gladesville in the 1860s that the gutters stank, toilets were overflowing, and that rats ran over the patients housed there. It’s a description that conjures up very grim images of grey stone, dirty clothes, rickety iron bedframes packed into the room, straitjackets, groaning and screaming people, and rats squeaking in the background.

Callan Park was to be an ideal – a revolution in care for the insane. The brain child of Dr Frederick Norton Manning and Barnet, the asylum was going to relieve the overcrowding in those older asylums, and do it better.

Stories of asylums are sad and morbidly fascinating for well-known reasons, and Callan Park has those too. But this story’s sad, additionally, because of how epically Manning and Barnet’s impressive efforts failed, as, by 1888, one year after the main complex opened, Callan Park was already overcrowded. Fit, at that time, to house a devil’s-number of patients (seriously, its maximum capacity was 666) it had 730, and by 1919, with more beds stuffed in and continued use being made of temporary Male Ward 7, built in 1877, they had 1300.

But I’ll start with the ideal, and hopefully paint a picture of it. Digging into this history, one thing I really wanted was a boots-on-the ground feel of Callan Park in the late 1800s – to see it, and understand it as someone standing there might have.

Dr Manning came to Callan Park with experience. Henry Parkes (politician, and later NSW Premier) had asked him to serve as Medical Superintendent of the Gladesville Hospital in 1867. Manning wanted an international tour of asylums first, and came back to Sydney after a year, influenced by the theory of “moral management” for the insane, Florence Nightingale’s teachings, and American Dr Thomas Kirkbride’s ideas on how to plan out asylums. Finding Gladesville about as appalling as Barnet did, Manning advocated for mental health reform and, in 1876, he became Inspector General of the Insane, a new post created because Manning recommended it.

At this time, a primary goal of asylums was to keep the blight of the mentally unwell out of the public eye. Manning and Barnet melded this with their ideals of best management for the insane: close connection to nature inside a pastoral setting, courtyards, fresh air, and meaningful work, with less physical restraint of patients. The parklands you can visit now were not only an attractive screen to hide the so-called lunatics, they fit the Victorian belief in the curative power of nature.

Frankly, I’m with them on this. Compared to the gaol-like settings of Gladesville and Parramatta, where patients packed into wards twiddled their thumbs and deteriorated, the Callan Park hospital, as it was meant to be, would be where I’d hope to go if committed.

Garry Owen House, built 1839 (later called Callan Park House) already existed on the site by the time it was prospected for an asylum. (No Garry Owen lived there, the builder being one John Ryan Brenan, so why it was called Garry Owen I can’t tell you, but Brenan was Irish, so maybe that’s a clue.) From 1876, it housed around 40 patients, spill-over from Gladesville, while the massive Kirkbride complex was built next to it. Behind Garry Owen house, a temporary wooden and weatherboard structure was built in 1877 to contain more and more patients. In 1878, Callan Park was its own hospital, and by 1885, it was ready for those 666 patients.

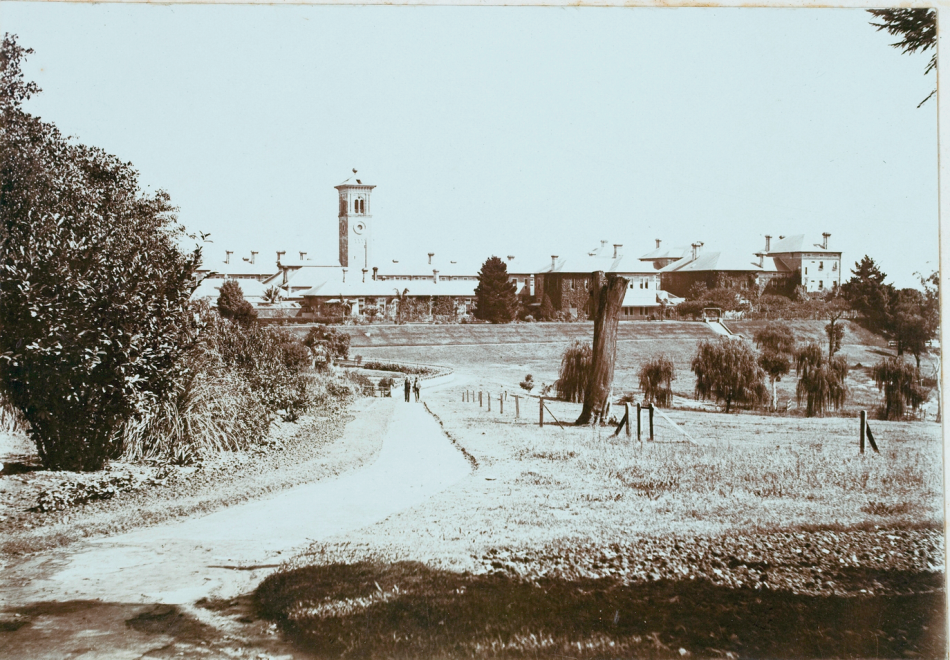

In the late 1800s, you’d enter through those Victorian gates into grounds part-constructed by the patients themselves. Pleasure gardens bordered the lane on either side, with, off to the left, a bowling green, cricket pitch, tennis court, and, somewhere on the grounds, was a herd of alpacas, for zoo therapy. Rising above is the huge Kirkbride Complex, an impressive structure, built of Sydney sandstone, that commands the high ground. A clock tower, ever sans clock (but with a water gauge) rises over the rooves of the front of the complex, partnered with a chimney from the boiler house.

Inside the Kirkbride complex, women’s wards are to the north, men’s to the south; the place constructed as separate buildings connected by walkways around internal courtyards. This allowed for both an airy atmosphere, and to separate wards so the “Male Quiet and Convalescent” ward wasn’t in the same building as the “Male Noisy and Violent” ward.

The views from ward windows stretch far, showing the waterfront and, as a skyline, the city. Both closer to hand and stretching into the distance were gardens and, for today in the inner west, unthinkable extents of bushland. For me, as a wannabe-hermit dreamer, the idea of being so isolated from a bustling suburb is whimsy in a daydream. I can’t help but wonder, though, whether for the patients, under the tranquil beauty of the setting was a sense of frightening I’m stuck here.

Going around the outside of the complex from the front entry to the back is a decent stroll. Down by the water were the vegetable gardens, on land reclaimed from the river. Here, and in the orchards or with the cows and chickens, patients are engaged in work that helps feed them. To the north of the Kirkbride complex are the convalescent cottages, originally three with a fourth added in sympathetic style in 1907. The night nurse’s quarters stood, towards the end of the 19th century, in a different though attractive style. Today, standing on that same spot, you see decaying 60s buildings in orange brick dotting the grass. Then, it was just a few sheds, and the cottages belonging to the gardener and farm attendant.

From what I can tell, there is an underground basement to the Kirkbride complex, and it does look like sequences of tunnels with areas that could have been used as cells. The scintillating legend of underground tunnels where patients could be hustled in undercover from the docks or as far away as Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, though, is a well-kept secret if true. There are the ruins of an old wharf though, where, for a time, Callan Park was receiving daily deliveries of patients from Gladesville hospital. Arriving as a patient, then, may have included a boat trip in place of a cart ride up through the main gates.

As for these patients, “insane” was rather a broad definition back then. One that included, rather than served as a synonym to, “mentally ill”.

“Insanity” at this time meant more things than we may think it to now. Late-stage syphilis was what put quite a few patients in Callan Park. At the time, epilepsy was considered asylum-worthy, as was dementia, mood disorders, and post-natal mental health concerns. The majority of patients in asylums – even many who were stuck there for decades – were not people with psychosis or violent disorders. There is some critique that some of them were there because they held unpopular opinions society thought intolerable then.

It is documented that, like Joe Masters, people were declared “delusional” because they were genuinely scared their poverty would mean they would starve.

While electro-shock therapy was slow to catch on at Callan Park, it was used to a small degree at this time, and that it wasn’t used more was considered a sign of not keeping up with modern treatments. Applying batteries to patients as a method of punishment, and, perhaps as some skewed sort of treatment, was practised before then. It was also considered a sign of the hospital being in the dark ages that they weren’t performing lobotomies.

As I’m sure you can tell, I’ve made rather a study of Callan Park. I’ve gone through and mapped out each and every building, and catalogued when it was built. Rather like the protagonist who introduces and bookends the story, I’ve walked those grounds, taking these photos, and wondering about times long past that are still with us in mouldering buildings sprawled out over prime real estate.

For some last notes, to finish this off:

One should never – ever – recap or reuse a hypodermic needle.

The use of “Mist. Sed.” is entirely real.

Long Bay, referenced in this story, is a prison in Sydney that still operates as a prison today.

Multiple bomb shelters are scattered across the grounds. Not enough to house all patients, it is nonetheless a mark of the fear all felt during the World Wars.

You’ll find further inspiration from Callan Park in my stories Rin. Sed. and Blurred and The Children of Somerton.

Everything stated in the preamble about Callan Park is true. And I still have not found a single image of the notorious male ward 7, nor any better information about why it is notorious.

There is still no approved plan for what to do with the derelict buildings mouldering away on the site. The University of Sydney, College of the Arts no longer occupies the Kirkbride complex, and headquarters of NSW Ambulance Service, which long made use of former wards 21 and 22, will be relocating soon, meaning those buildings too will soon be left to ruin.

Attributions:

Podcast intro and outro music:

The Dark Tile , by Rafael Krux. Full licence purchased.